Movies I Watched May 2025

Ash Is Purest White - dir. Jia Zhangke

NOW we’re brothers. Now after the tides have risen up the Three Gorges and sunk most of the vista underwater. Now that the gun went off, now that murder was heavy on my brain, the weight of time ceaseless, NOW we are brothers. NOW you wish to proclaim your love.

Men ain’t shit; a wuxia flick. Honor ain’t shit; aliens are real.

Forging purity through magma. Prison sentences, buried in the earth, erupting to nothing. Ash coats the fields, the world is buried under lava but chip away at its past and you find nothing but history; time is ceaseless. Time moves without a care for the age it wreaks.

Wrong hand. Wrong hand indeed. 9/10.

-

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom - dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini

Just found out about fascism that shit is crazy

4/10.

-

Love Liza - dir. Todd Louiso

Incisive in its depiction of social norms surrounding grief, how we simultaneously behave more permissive of antisocial or mentally ill behavior when the pall of death hangs over but also resent the burden that grieving people place on society.

Good, sad vibes but this just did not make me feel all that much. I think if it was directed by someone like Jun Ichikawa it could’ve been a masterpiece.

-

Bonjour Tristesse - dir. Durga Chew-Bose

We have Luca Guadagnino at home type shit

4/10.

-

Excalibur - dir. John Boorman

Buncha British blokes playing dress up. Like if Conan the Barbarian had nothing remotely compelling about it.

-

The Human Condition I: No Greater Love - dir. Masaki Kobayashi

Through the dialectical negotiation between ideas and material realities, both sides of the barrier, two halves of a whole–theory versus praxis, Masaki Kobayashi constructs the nihilistic excelsior of critique on the liberalist worldview. This is a film that is fundamentally and expertly about the failure of liberalism to meet a totalitarian regime at any meaningful level. As a demonstration of cinema mastery, you do not get movies like this very often. I have my score as “low” as it is because I find the objectives of the film personally unappealing (I’ve got low tolerance for this sort of exercise in nihilism), but I open my heart for the possibilities of the two next entries. Perhaps I will be proven mistaken in my estimation of this film’s pessimism–regardless this is some of the greatest filmmaking to ever grace the art form.

I don’t like to ascribe shallow praise (very easy to say WOW GREAT FILMMAKING) so I’d like to try and explain WHY I am so impressed by craftsmanship.

First; when Kobayashi establishes the scene he cuts highly intentionally. When he does shot-reverse shot, it is never in service of the dialogue itself. A good example of this would be the scene in which Kaji talks to one of the Chinese POWs inside of the barbed wire barrier. Kobayashi cuts between them to establish a spatial disconnect, but both of their faces are framed by the wire–they are both imprisoned by the system.

Even though Kaji is enlightened by comparison to his totalitarian comrades, he is still abetting their reign of terror by behaving in complicit with the cruelty. Merely by accepting the position they have given him he is playing by their rules–and he continues to play by their rules the entire film. His efforts to help the prisoners are meager and exist through only authoritative channels. His liberal morals prevent him from breaking the rules. Even when the prisoners attempt escape, he does not “help” them, he just refuses to “harm” them. One might ask… would they have succeeded in escape if Kaji had decided to help?

When Kaji marches towards the door, his wife holds him back, begging him to stay, to not forfeit his life for the prisoners. A noble woman, a kind husband, a failure to fight the institution. Not on Kaji’s part, he does try his best. And his wife is in love with him, why wouldn’t she want the best? But this is the crux of liberalism’s inability to fight fascism. The fascist forces you to choose between the false dichotomy of freedom or your family. The liberal, unable to think outside of their individualist framework, secedes ground. Kobayashi frames the domicile as a prison, blocking Kaji and Michiko like caged animals. The marriage is a trap to prevent radicalization. When Kaji is tortured, his tormentors hold his wife around his neck like a noose; what would she think of the screams? Who will hold her at night when you are gone, executed, sent to the front lines? The individual is powerless against such threats, the individual breaks.

I return to the suggestion of No Greater Love as liberal failure; in the harrowing scene of execution–which Kaji is individually powerless to prevent, having exhausted several institutional means before arriving at the moment of climactic carnage–it is the PRISONERS by their collective might that succeed in halting the execution. It is the PRISONERS who strike fear into the hearts of the outnumbered guards, who are quashed in their fervor not by politics or policy or pleading but by the will of the oppressed themselves.

Kaji is a good man, Kaji is a kind soul, Kaji is a pacifist, Kaji is a stand-in for Kobayashi’s beliefs and so the film tends to side with him, but Kaji is also a failure at achieving meaningful results and I believe on some level Kobayashi is aware of this fact, so when he frames Kaji on the day of reckoning, Kaji is in the foreground while Kao, the victim of execution, is in the background. The depth of focus makes them parallel versions of one another. Both crushed by the same totalitarian boot. The same totalitarian boot will later torture Kaji within an inch of his life and give him a similar scar to that of Kao’s–down the temple. The fascists are indiscriminate in their malevolence. The target will be whoever the war machine decides is the enemy. The Chinese, sympathizers to the Chinese, they are indistinguishable to the fascist.

On a metatextual level the existence of the film is itself a moral paradox. Often, Kobayashi will frame Kaji as an observer, a voyeur of suffering. His character is defined by the aforementioned dichotomy of theory vs praxis. He is excellent at speculating on suffering, he is excellent at diagnosing evil, just as the film enthusiast can eagerly identify the evil portrayed in cinema, but when Kaji is thrust into the reality of suffering, the material bleakness of suffering, he is overwhelmed. His intellectuality is helpful to a point, and then it works against him. We delve deep into interlocution, but forgo intervention. Immediate action is postponed for endless dialogue.

Kobayashi, at the end of the film, has Kaji proclaim “I hope they all get away,” while looking at a picture on the wall, as a response to the military officer who tells him of the escapees. Nothing has really changed for Kaji, he is still just as wrapped up in the facsimiles of praxis, invested in watching the struggle occur from afar instead of getting his hands dirty. Again, he is a good soul–but he fails to follow through on his principles. Theory and art are powerful, it can stand the test of time and inspire greatness even centuries after its creation. Kobayashi’s work is a testament to this, his films have long outlived the totalitarianism of early 20th century Japan, and Kaji is able to help the prisoners some. But fundamentally, it takes a huge collective effort to directly conquer and overthrow evil systems. It takes action, it takes, at the very least, the threat of violence, it takes the will of hundreds, if not thousands, if not millions… if not billions. 7/10.

-

Mean Streets - dir. Martin Scorsese

De Niro is rightfully considered the GOAT but this is a top 5 role for him and I feel nobody talks about it enough. I don’t know why but he scares me here almost as much as he scares me in Raging Bull.

-

The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity - dir. Masaki Kobayashi

Probably the worst opinion of all time or whatever but this didn’t click with me. Too binary, too one-note. 3 stars are for the ambition and for the few scenes that struck a chord, like the scene where Kaji has to decide whether or not to let a guy die in quicksand. 6/10.

-

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore - dir. Martin Scorsese

Feminism is when all women do is cry a lot and yell at their kid and occasionally get so exasperated with the experience of life itself that they settle with a giant douchebag and have a few meltdowns along the way. Scorsese’s misandry actually works better when the men are the main characters tbh. 4/10.

-

Hurry Up Tomorrow - dir. Trey Edward Shults

Trey Edward Shults is one of those manneristic impersonators of better directors, sort of in the same boat as a guy like Francis Gallupi. All simulacra, nothing original, empty impersonation of technique without any soul. You like one takes? You like neon lights? You like uhhhhh PSYCHOLOGICAL HORROR? One “art house” film coming right up, sir!

I guess the blame shouldn’t be placed squarely on the shoulders of Shults, obviously this is a Weeknd vanity project first and foremost, a terrific display of what happens when the most creatively bankrupt person gets carte blanche to make middlebrow music video bullshit. The Sam Levinson of it all, man. We really need to abolish therapy, this much navel-gazery can only come from a culture that has been hermetically raised in a chamber of self-affirming balderdash. This shit is what happens when mental health becomes a brand and not something you deal with on your own time. Imagine making a whole movie about your fucking genital warts. NOBODY CARES ABOUT YOUR MENTAL HEALTH. NOBODY CARES ABOUT YOUR TRAUMA. Take your meds, go to therapy, scream into a pillow, do NOT make entire movies about yourself. Unless you are Orson Welles. Or Albert Brooks. Or Hong Sang-soo. Then it’s fine.

What the fuck are we even doing man. Why are so many auteur directors totally fucking worthless? Imagine being so spineless as an artist that you willingly direct Weeknd trauma porn. Imagine writing this script. Imagine shooting the scene where Jenna Ortega reads Weeknd lyrics analysis off a ChatGPT prompt. I would go home and shoot myself. 2/10.

-

Until the End of the World - dir. Wim Wenders

2 stars for Robby Muller. Motherfucker carried.

One of the most lowkey sexist movies ever I feel? Seems like it gets a pass for being quirky but I found Claire to be horrendous. The back half of the film is really insulting too, because all she does is hang around like a dog that nobody cares about, with no goals and no purpose. There’s a scene where Farber starts crying about his tragic backstory (obviously he’s a momma’s boy) and the camera cuts back to show a NAKED CLAIRE WALKING INTO FRAME LMAOOOOO like this is supposed to be the character that drives your narrative and instead she is there to reward a man with sex for loving his mom.

Obviously this is just one scene, I don’t like nitpicking individual stuff, but christ, when your whole movie is built on a man narrating his ex-girlfriend’s adventure (this gets VERY condescending later on, when he hands her his finished manuscript and she’s like… what’s next 🥺…. and then he puts a hand on her cheek and says “whatever you choose to invent”…. or some stupid fakedeep bullshit. And then she starts crying. LOOOOOL. Give me a fucking break). And on TOP of that, Claire’s built up to be this agent of change who inspires the people around her (or something?) but her entire motivation revolves around a man to the point where once we get to the last 2 hours of the film she has NOTHING to do??? Like you could say she’s the only one who can operate the tech because of her advanced memory or mind imaging or whatever but that’s not really true, they all end up equally addicted to the dream tech anyway so it’s worthless.

Beyond the patronizing sexism, I find several plot points abysmal–like the whole end of the world gimmick never feels relevant at all. It’s like they build up the nuclear bomb, we never see its effects, we never feel the characters starving in the desert or anxious about the end of the world or anything, it’s merely paid lip service to in the script. And I dunno, I just feel like if you’re going to depict the end of the world… depict it? But of course the film reveals that there was no nuclear bomb anyway so the whole thing is a pure aesthetic exercise. Nonsense, bullshit, waste of time. Why is this five hours again?

The movie starts off promising with the “ultimate road movie” conceit, like I’m all about characters traveling and vibing, but the issue is that at the 3 hour mark, once the misogyny and quirky bullshit wears you down, you start wondering–hey is this gonna build to anything? Is there a direction? Every road movie has a destination, even if the destination changes or mutates it exists for a reason, so when we get to Australia and it’s 2 hours of shitty music by side characters we don’t give a fuck about and Claire hanging around Sam like a stray puppy while we deal with daddy issues (ugh) and how much he loves his mommy (why does he make out with his mom again?) I’m like… what the fuck is the point of any of this? Like yeah the shots are pretty but these people are all different shades of annoying and the sci-fi is scarcely touched upon, plus it all ends up being a metaphor for addiction (ugh), so who cares? Why should I care?

If you enjoyed this, cool, sick, good for you, genuinely, but for the life of me I cannot stand this caucasian quirk fodder. Wim Wenders has never REALLY impressed me and I figured out why here–his movies reek of inauthenticity. They are colorful postmodern character studies barren of character.

Paris Texas still pretty good tho. 4/10.

-

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre - dir. Tobe Hooper

Backwaters of America, where mass culture is produced; head cheese, made out of the leftover organs from the endless procession of slaughterhouses which decorate flyover country for acres and acres. The affluent hippie kids are inauthentic, they’re willing to consume but they don’t wanna know where the shit they consume comes from. The psychos in the south may be deranged lunatics, but they’re the backbone of this nation. They keep it real. 8/10.

-

The Human Condition III: A Soldier’s Prayer - dir. Masaki Kobayashi

This whole trilogy rubbed me the wrong way, if I could intuit the reason that’d be great, but I’m comfortable just saying that I found it irrepressibly boring.

-

Paradise Now - dir. Hany Abu-Assad

Whole time I watched this I wondered how Zionists would react to it. How would they rationalize the occupation? I think my parents would side with Suha. Something about how the tragedy of the occupation is real but terrorism is not justified as a response, blah blah blah.

We’ve all gotten a little too comfortable with a society divorced from oppression, I think. It wasn’t so long ago that African slaves were killing people to revolt against bondage, and it was less than a century ago when Jews being rounded up into Polish ghettos threw molotov cocktails at German soldiers as an act of resistance.

People pushed to desperation behave violently; it is a story as old as oppression itself. I am ashamed that I ever rationalized Israeli fascism, but better late than never.

Free Palestine.

7/10.

-

Ó Pai, Ó - dir. Monique Gardenberg

Wants to be Spike Lee, and because of that I think you enjoy this a lot more if you speak Portuguese

-

The Aviator - dir. Martin Scorsese

Scorsese’s most Eastwoodian film only in the sense that it pits the American man against the American system–the ideals of America face to face with its reality. A tycoon who made the biggest movies, the biggest planes, slept with the hottest women, facing scrutiny from the big government, which is in bed with the other capitalists.

“Everyone works for you,” but the Randian, obsessive-compulsive delusions persist, all your ambitions the outpouring of fear of a distant motherly memory.

Weirdly, this is Scorsese’s most epic film, more epic than Goodfellas or Killers, it sprawls an interminable time in the life of a man who is driven to madness by his own ambition. A Greek tragedian tale where psychology is only really important in casting a shadow under-girding the luminescent, explosive bulbs shined over a legendary figure.

The way Scorsese shoots light in this film is pure horror; overwhelming, crunchy, visceral. 7/10.

-

Black Christmas - dir. Bob Clark

Whoah. I think I can get behind this–the slasher that also functions as a character study, that also acts as a room tour of the sorority house, possessing a keen sense of place. Feels cozy but also deeply unnerving. Some legitimately scary moments laced in shadow. 7/10.

-

The Departed - dir. Martin Scorsese

Abandon the mortal plane or the moral plane? Card trick cinema, more a matter of script-heaving spectacle that braces on its own layers of deception until you’re lost in the goose chase, at the mercy of the magic trick. Costigan and Colin are themselves magicians, spinning lies to their associates as easy as apple pie and frankly it’s almost superhuman to watch them keep their narratives straight. Costigan’s almost exposed by a dying guy and it’s a miracle he isn’t.

I don’t like that Scorsese positions Costigan as the good guy and Colin as the bad guy, he gives this whole thing a “morality tale” vibe that dilutes from the film’s obvious dualistic narrative. Like the whole point of the switcheroo is that the script is drawing a connection between the cops and the criminals. Costello literally works for the FBI so any idea of real justice at the hands of the law is subverted from that point forward. And Colin getting punished for being a rat (with the very, very subtle shot of the rat crawling on the balcony in front of the church after he is karmically assassinated by Dignam) strikes me as a fairy tale outcome. The rat getting his just desserts.

But riddle me this–if it was so easy for ratfuck Colin Sullivan, groomed by Frank Costello himself, to penetrate the highest levels of the police department, what does that say about the institutions themselves? What does it say that Costello holds more value to the law than the guy sacrificing his life to bring him down? 7/10.

-

Venus in Furs - dir. Jesús Franco

Ouroboric recursivity in the land of the dead, the transient feminine mystique slipping through the fingers of all that try to possess her… to control a woman’s body is to forfeit your soul forever, to play music to the endless parties at the various levels of hell.

What I find most exciting about Franco’s direction is the impulsivity, it actually reminds me a lot of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s rejection of cinematic formality. Or maybe it’s the opposite, fully leaning into the world of the camera so as to take the medium to the limit of the imagination? I digress–the point is, I love the carefree devil-may-care directorial approach with which Jesus Franco captures an erotic encounter, or the realization of one’s own masculine futility. The ending runs the risk of alienating its more self-serious audience members, but because it is so beatific in its weirdness there is no way to view it as anything other than the celebration of the ultimate seductress.

I also find this movie Catholic as fuck lol–the idea that pursuing lust will take you straight to hell. Didn’t slip by me, that’s for sure. 8/10.

-

The Irishman - dir. Martin Scorsese

For the first hour and a half I was just passively engaged, and then as the chips fell and the weight of each sequential moment stacked up into something historically formidable I was rapt as could be. I felt like I was hovering on autopilot for most of the standard Scorsese milieu, the old man playing the classics for a summative rodeo, so to speak–the experience mirrored by Frank Sheeran who coasts on a shiftless moral code through the decades, literally on emotional autopilot as his friends die around him, as he is sent to kill Hoffa, who is his own soul. The ultimate tragedy is the assimilation of ethics, the breakdown of culture, the absorption of a man into the tapestry of life, until he is just one old man in the corner whispering dreams back to himself.

You get to be a centenarian and what do you have to show for it? A lifetime’s worth of mistakes, burnt bridges, bodies, jobs well done. Scorsese proposes the idea that there exist a cumulative series of events that kill the soul of a person or a nation, and usually the two coincide in some way. And the tricky part is that you won’t recognize it as it’s happening, only when you look back at the wounds you can pinpoint the thousands of cuts that bled you out into a husk. Nothing is so compelling to me as the weight of time, and the Irishman feels like an essential part of that canon, the tacit power of an ultralong film to stack the bricks until the past has been set in stone. 9/10.

-

The Others - dir. Alejandro Amenábar

I find this kind of horror unbelievably lame but I do respect the craftsmanship. As far as studio-produced work goes it gets much, much worse.

-

Ride Lonesome - dir. Budd Boetticher

Instead of talking about the psychology of the cowboy, or what a Western says intrinsically about the mythos of America, both of which are worthwhile endeavors, but not suitable for what I wish to focus on here. Really, politics are not as important to me with this film as is the stark beauty of it–finding out that this was a B picture back in the day is absolutely mind boggling, as it is one of the most beautiful westerns I have ever seen. As a no budget filmmaker it is VERY inspiring. Stuff like this reaffirms to me why I love shooting out in nature so much. It’s inherently beautiful, I don’t have to do much work to elevate it. I just ask my girlfriend to set up the tripod wherever she feels she can get a good shot and we’re off to the fucking races. 7/10.

-

Irma Vep - dir. Olivier Assayas

Having gone into pre-production on my first “real” short film, i.e. a crew, a cast, locations, etc. I feel my view on the medium has changed a tad. No longer am I a slave to the delusions of full auteurship, I must recognize that outside the purview of the director’s vision the art form is inherently democratic–the process by which a masterpiece is crafted is rarely via one laborious hand but by passing through many. I don’t reject auteurship at all, I still believe in the directorial vision and I am excited to bring my own to MY film, but I also feel consigned to admit that at a certain level, the film stops being “yours” and by the mere chaos of production is absorbed by everyone else. Then, even when you gaze upon the final product, it’s never quite what you had in mind, never exactly what you thought it would be.

Filmmaking is so fraught with mistakes, it is almost impossible to get exactly what you want out of a shot or a scene. Actors will make mistakes, sound will get disturbed, you will have to record ADR to make up for it, and in the end you’ll have to edit the project with whatever scraps you were able to scrounge on the all-too-short days of shooting. I think the end of Irma Vep is beautiful because it is beatifically self-destructive, recognizing the delicacy of the film roll while also noting its resilience. The final product is a complete mess, but it’s wonderful too, it is something that never could’ve been painted or written. Only in the infinitesimal variances of the camera and the people behind it could such a piece of art have come into existence. 9/10.

-

The Last Wave - dir. Peter Weir

I cannot imagine a less tactile approach to a story of Aboriginal mysticism, how are you going to take such a phenomenally apocalyptic conceit and turn it into a paint-by-numbers legal drama? Further proof that British and Australian filmmakers are mostly worthless. 4/10.

-

The Naked Spur - dir. Anthony Mann

Robert Ryan is unreal here, just psychological warfare made manifest in a person and it’s insane watching him operate on our “protagonists” (a word lightly tossed considering the moral murk we’re talking about), getting them to turn on one another. “The longer we ride, the more things that can happen.” The landscape imposes the psychology. This is the flipside of Leone’s western where humans try to impose their pathological state on the environment (the Man With No Name manipulating the two gangs against one another in Fistful, the train tracks being built out into the frontier in Once Upon a Time). In Mann’s western it is the environment which builds into the brain. The outlaw and the hunters perpetually react to what the environment throws at them, the trick is to figure out how to disguise your intentions and actions with the world around you. If that means using a cave-in to escape or a river to claim your quarry, so be it.

And yet I wouldn’t consider this film to be a story of Man vs Nature. Mann positions the economy of unsavory exchange (life for land, truth for cash) as a dynamic that places people at each other’s throats by proxy of perspective and distance. Everyone wants something, everyone else stands in their way. The frontier is merely a landscape to sketch these nebulous pursuits onto. Anthony Mann does not care about psychology insofar as it is able to highlight the physical exertion of its will, what your greed pushes you towards and how it warps the world around it. This is a world in which your greatest enemy, both for yourself and for the territory you yearn to possess, is other people, and the only way to earn your stake on the land is to outfox the opposition.

Weirdly, I feel like Anthony Mann is anti-spiritual in his portrayal of life and death. It’s weird because usually I prefer a bit of spirituality in my Westerns, even if it’s fleeting, but Mann’s hard-nosed depiction of intersecting ambitions REALLY works for me. If everybody is a bargaining chip, then the afterlife itself doesn’t matter. The only value the afterlife holds is in that it is a release from the competition of life. “Choosing the way to die, what’s the difference? Choosing the way to live, that’s the hard part.” Death is an easy way out, it’s the cosmic solution to the question of how do you figure any of this shit out? Answer: You don’t, you die, everything is simplified. When Ben kills Tate, he says, “Look at him. Lying there peaceful in the sun. Ain’t never gonna be hungry again. Never want anything he can’t have. That’s more than we can say.”

Kemp’s real struggle, then, is not whether he can survive the frontier, but whether his self-perception can survive the hunt. Can he forgive himself for selling a man’s body for cash? Only the pure heart of a woman can redeem him in the end. 8/10.

-

The Squid and the Whale - dir. Noah Baumbach

A piece of my soul will always identify with the films of Baumbach because he narrows in on such a particular kind of Jewish identity. Not one I fully identify with, but enough that when Jesse Eisenberg talks about his fond memories of seeing the Natural History Museum’s still life taxidermied exhibits with his mom I will feel this welling sensation in my chest. My parents are nothing like these parents, my brother and I’s relationship bares scant resemblance to the brothers here, but there is still such a razor sharp specificity that I can draw myriad through lines between my own life and theirs. It’s a special work, not as emotionally wrenching as Marriage Story but far more relatable to me. 7/10.

-

Morris from America - dir. Chad Hartigan

Couldn’t finish, super lame.

-

Hotel Monterey - dir. Chantal Akerman

A great reminder that nobody is too good for a soundtrack. Unbelievably boring. A neat experiment, though if your goal is to capture the essence of a location (which I presume was the goal, though maybe ascribing a goal to a piece of art is too limiting) you should absolutely incorporate sound, music, noise, etc. 5/10.

-

Hiroshima, Mon Amour - dir. Alain Resnais

Breathing, moving cinematic memory, encompassing the incandescent beauty of all living things. The acknowledgement that all history becomes an act of remembrance, and all acts eventually fall out of style. Time chugs forward. The diocese passes hands from one bishop to the next, the moral battle for nuclear war remains forever on the precipice, the kisses on the neck fade into the skin, absorbed by the passage of life into the next. Resnais’ cinema is some of the purest–you may not find a more ephemeral source of dreamlike heartbreak on this planet, and I really believe that’s what movies are about at their core. 8/10.

-

The Funeral - dir. Jūzō Itami

Got me thinking about the strangeness of death, how our little meat bodies end up as uninhabited husks, sent into the pyre with elaborately ritualized ceremony. This movie is so GOOD in the purest of senses, Itami is so obviously skilled at what he does that it’s hard not to get wrapped up in the mise-en-scene of it all. The way the characters move through the shot, the way he pans across their feet as they shift uncomfortably, just terrific stuff. Japanese cinema is so good it makes me overlook the war crimes. 8/10.

-

Fat Girl - dir. Catherine Breillat

Criterion Challenge

-

The Fly - dir. David Cronenberg

Misinterpretations of output from technology inputting flesh and being unable to fully process its complexities, or how love is corrupted by machines, more or less. Maybe the most romantic Cronenberg movie? I can’t remember being more devastated about it not working out in any of his other films. Brundle and Veronica are sweet. I always like Goldblum pictures because he’s one of the few sincerely Jewish sex symbols. I relate! 8/10.

-

Night of the Living Dead - dir. George A. Romero

Terminally boring–a film that is likely more interesting to hear about or read about than it is to actually watch. I heard all about the subtext and how it influenced all horror that came after it and then I see it and it’s just straight up ass. Zombies suck, actors suck, editing sucks. I don’t like writing these kinds of reviews but wow this is a stinker, just NOTHING compelling. 3/10.

-

Dead Ringers - dir. David Cronenberg

The soul bifurcated into two bodies without anywhere to go but through the middle. How do the bodies negotiate sharing a soul–how do they negotiate sharing a life, a career, women, objects, things, tools, et al. With Cronenberg I feel I have to look through the weirdness sometimes to see the beating heart at the center, here there is an aching sense of ache itself. Pain. Oscillating somewhere between dulled in the corner and bright in the center of the frame, a violent penetrating force in the loins. 7/10.

-

Gemini - dir. Shinya Tsukamoto

It pisses me off that Tsukamoto does NOTHING for me as a director. I wanna like his movies so bad but they feel like dull noise.

-

Maps to the Stars - dir. David Cronenberg

At its very inception, the core elements of Maps to the Stars are fire and water and how they interact. Fire gives birth, painful as it may be, the end of one life into the next, the birth of a family’s sins–“you should have gotten a restraining order when she was born”–and water is death, cold and careless–that moment when the ghosts of the dead children thunk into the water. Except there is no sound, and that’s even eerier. Their bodies give no indication of breath or life, they simply enter the water without a ripple. Death.

It’s easy to say the system creates sociopaths. Just because it’s easy doesn’t make it less true, but if you dig deeper you’ll see that the scary part is not that the system creates sociopaths but that we learn to take comfort in the sociopathy itself, we learn to define ourselves around the “core” memory, the single instance of tragedy that outlines the rest of our lives. For Benjie, it’s getting groomed by his older sister, for Havana it’s her mom’s abuse, for the Weiss family at large it’s the fire started by their wayward schizophrenic daughter.

You’ll see that Havana lives for the abuse, she designs her life around it, the thing that brings her the greatest joy is getting to live in the psychology of her abusive mother. She runs in fear from the ghost but she yearns to enter her mother’s mind. I might be reaching but this might be a way of calling out the rationalization of cruelty, how we think we want to understand evil but run from it as it rears its ugly head.

Perhaps the comfort comes from the authenticity of the insanity. The only person who is able to reach through to Benjie is the sister he “married” and that’s because there’s no rationalization. Crazy simply understands crazy. 9/10.

-

The Double Life of Veronique - dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski

Utter garbage. Color grade out of hell. I fucking hate surrealism like 99.9% of the time, this shit is ass. Stuff needs to actually happen in your movie even if nothing happens. I cannot stand when it feels like I am watching a procession of quasi-philosophical bullshit. It is increasingly apparent to me that the only filmmaker on planet earth capable of making quirky surrealism work was Lynch (rest in peace), and even his work pissed me off occasionally. With Lynch at least there was a pulpy genre coating that gave structure and weight to the surrealist proceedings. Inland Empire is a horror film, Blue Velvet a mystery, Lost Highway a thriller of sorts. Watching this piece of shit, on the other hand, feels like hearing about somebody’s dream; boring as shit and a complete waste of everyone’s time. If a movie is ever described by a chud as “rich with symbolism” run like the fucking wind. 2/10.

-

Crimes of the Future - dir. David Cronenberg

As is sometimes the case with Cronenberg, I find less fascination with his actual films than the ideas he presents. The presentation here is just too dry. A smorgasbord of conceptual toycraft, more for the hardcore Cronenberg fanatics than for somebody who just “likes” him. 5/10.

-

Ugetsu - dir. Kenji Mizoguchi

Men chase foolish dreams, leaving their women to suffer cruel misdeeds in a world built on the ghosts of dead warlords.

This wasn’t quite as haunting or spiritually elegaic as I expected, but it is still further confirmation that in the presence of Mizoguchi, we are all mortals. 8/10.

-

Final Destination Bloodlines - dir. Zach Lipovsky, Adam B. Stein

COSMIC HORROR DISGUISED AS SOME BOZO SHIT = FUEGO

THE SINCERE SHYAMALAN FAMILY PUT THROUGH A SOCIOPATHIC RUBE GOLDBERG MACHINE = GASOLINE

Pure gold. It’s crazy how much better horror is when you are invested in its characters. I was trying to pin down the whole time I was going so buck fucking wild for this movie until I realized it was making the adult me feel comparable to the child me watching Aliens in the Attic. The same goofy, creative setpieces. The same likable family.

It’s not the same as nostalgia-bait because there’s nothing about this that directly ties to nostalgia–it’s simply a well-crafted populist film that commits to its own premise. Yo, what if there WERE aliens in your attic? 9/10.

-

The Wind That Shakes the Barley - dir. Ken Loach

Lotta “acting” in this one

5/10.

-

I, Daniel Blake - dir. Ken Loach

I used to like kitchen sink political realism at the onset of my film life, and sometimes I miss the hopelessly inert myopic narratives occupying the various echelons of European festivals, how much I used to feel they “educated” me, but now I just don’t really care about these kinds of stories, tbh. Ken Loach was a director I thought I cared about a couple of years ago, when Old Oak was something of a revelation–now his work seems flat. You don’t need to watch his films, listening is enough (not a compliment at all), and this is a record that repeats itself over and over again. 5/10.

-

Sansho the Bailiff - dir. Kenji Mizoguchi

And we were born, and we made tools, and we learned about power, and we built the catechisms of our nascent civilization on its wings. The intangible quality that lets one man hold power over another. From the first stick raised in defiance of the Olympians to the first time we glimpsed another galaxy, we fought and killed to determine what belonged to who. And we were born, and we made rules, and we learned of the sword, and the spear, and the bread that leavened in the ovens, the bread that came from the labor of billions. Toiling peasants on the land of the monarchs, saddled with the baleful gazes of the guards posted around the manor, as far as the eye could see. And we were born, and we kept our heads down as the katanas swung, and we lived and we died for the procrustean kings; lords of the hay, branding the weak, drinking the wine.

History was a wind that carved granite into statues, architecture into dust, dust into wind again. Children were born and chiseled into men and women, broken down into skeletons, their bones repurposed into steel that lifted the war machine into flight. Identity transient when it is bent in the forges of time.

And Mizoguchi says; it is the unseen cruelty which defines the world. It is the violence under the surface which swells and maintains the sadism of civilization. It is the sign that cannot be read, the law that is wordlessly enforced by spear, it is the hot iron pressed against the face of an offscreen slave by another slave, to keep them both in line. It is that the film is named after the perpetrator, it is that history goes to the victor, it is that time sides with the powerful, it is that we give remembrance to the kings but not the servants, the emperors but not the messengers, the generals but not the soldiers.

Possibly the greatest film ever made, Kenji Mizoguchi cements himself to me as the absolute king of the cinema. The untouchable master. If I can be a hundredth–no, a thousandth–the director he is, I can consider my artistic aspirations to be worth a damn.

Compassion, mercy, and kindness are anathema to power. When Zushio is made governor, it is not a joyous occasion; the music is eerie, as if to suggest the uneasy possibility that in his power he will be consumed by its tantalizing cruelty. Later, he relinquishes his title in search of the boy he once was. All kings were once boys. All tyrants once infants suckling at the teat.

Zushio gives the slaves freedom. But we must ask how long will it last? How long until they are reclaimed? How much will it take to destroy it everywhere? And yet in the anarchic bliss of celebration, Mizoguchi gives us a morsel of hope, that perhaps the systems can be eradicated for good, that perhaps we can overcome the barbaric instinct for hierarchy, this system which is overwhelmingly meaningless–a system which assigns humans with arbitrary god powers and just as easily strips them away. A woman and her children one exiled husband away from slavery, one slip of paper away from regaining their lands. It’s all so fucking pointless, isn’t it? Just a way we can organize ourselves towards the top, pyramid up, the billions at the expense of the few and for what?

“A governor isn’t authorized to interfere with a private manor… carefully reconsider your limitations.” The freedom is forbidden. The freedom is earned not by words but by blood. Not by law but by physical will, imposition, attack. I return to the winds of history. The winds which shape us, the winds which erode us, the winds which shuffle the deck. I ask, what is our world but what we choose to build out of it? Mizoguchi offers the full weight of history and the suggestion that it can be transformed and manipulated into new matter. The literal reconstruction of time itself. Maybe hierarchy can be flattened, one day. The fight is eternal. The war for the soul of man is fought in every breath and every movement of every human on this earth. We inherit the fight of our forefathers, but the tides can change in a heartbeat. We may become unrecognizable to our mothers, we may be so corroded by the waves that our voices go hoarse, we may even find ourselves alone at the end of the world, but in the embrace of love almighty, we preserve the soul for all time. 10/10.

-

Hardcore - dir. Paul Schrader

This film feels weirdly constrained by studio sensibilities. For a film called Hardcore it does not at any point feel very hardcore. It dips its toe into the skeeze and the grime but never submerges itself fully. I can understand why Schrader himself would hate rewatching it because as a more mature director I can imagine so many more formally daring ways the subject matter could be approached by him in the later years of his career.

I get the sense that this is a film he wrote and directed as an act of therapy more than anything, and to be honest I’ve been there too. My first script I ever wrote is borderline unreadable to me because it stinks so deeply of the desire to cleanse my own personal self. At the very least Hardcore is not totally autobiographical, I think Schrader would probably identify more with the runaway pornstar daughter than the conservative capitalist father.

-

Hollywood Shuffle - dir. Robert Townsend

This is the exact movie that every CSUN film student aspires to make, and lowkey this is the best version of that–satirical genre splicing and an attempt at social commentary that sort of works but doesn’t feel fully transformative. I don’t know. I thought this was a likable movie for sure but the SNL style parodies didn’t do much for me. It’s got its heart in the right place though. 6/10.

-

The Leopard - dir. Luchino Visconti

Dense as a motherfucker–you’re really not going to get a lot out of this if you spend your time trying to pick apart the intricacies of 19th century Italian politics. Luckily, Visconti is a director driven not by words but by images. Not that you needed ME to tell you that… But it is worth saying that the story tells itself, the interpersonal power dynamics are not crucial to understanding the thematic backdrop. Though I do still intend to read some analysis of this film so I can get a better idea of it.

Fundamentally the entire film can be boiled down to the ballroom scene. The pageantry of Italy’s upper class in gross excess. Untouched lobster, untouched cherries on top of untouched cupcakes. A morbid amount of food for an interchangeable elite.

I am still forever awestruck by Visconti’s attention to detail when it comes to mise-en-scene. In terms of what I consider to be great filmmaking, he is possibly the greatest ever. When I think about it, Luchino Visconti is who I aspire to be as far as fundamentals go. Wide shots, lots of happenings, highly intentional cutting, compositions like prisms with set design that rewards the exploring eye. 8/10.

-

Suicide Club - dir. Sion Sono

Promising Y2K vibes for the first chunk, then we get Japanese David Bowie stomping on puppies for no reason and I am reminded that this is a film directed by the hackiest of hacks, Sion Sono. I wish this exact film was made by Kiyoshi Kurosawa instead, or possibly… wait for it… Harmony Korine. 6/10.

-

The Book of Life - dir. Hal Hartley

Poorly preserved DV by Hal Hartley. Immediate comparisons to Inland Empire but beyond aesthetics the parallel falls flat. I’m not typically a fan of pseudo-intellectual art house bullshit–either give me something tangible or go fully abstract–but Hartley’s aesthetics are as strong as ever. 7/10.

-

Death in Venice - dir. Luchino Visconti

Perhaps this is a pedestrian view of the film but I don’t see it as a tale of pedophilic lust, even though the read has validity. I see it instead like I see all of Visconti’s work; a tale of troubled aristocracy, and the untangling of the binding social threads of feudalism as it transitions into populistic fascism. That much is clear by the stubbornly dogmatic composer Gustav negating the spirituality of art and his view of the young Aryan teenager as the object of pure body. It is no coincidence that one of the posters for this film features Tadzio as a Romanesque statue carved out of marble; it is less that he is being lusted after sexually and more that he is being heralded as an item of romantic purity.

Visconti often shows how his aristocratic characters fumble with the decline of their world’s social order–as an older, sickly man Gustav must figure out a way to remain purposeful in a society that is quickly shoving him off to the side. I saw a great review by @KaoriKap that pointed out the extra-European forces destroying his perfect vacation–the pestilence from the East, the sirocco from Africa. As clear as can get this is a film about a man in freefall and holding onto aryan purity as a kind of last ditch effort at producing a muse. Of course, this gambit destroys him, as fascism tends to do. He attempts to recapture his youth, to die his hair and to pomp his face with powder, but one of the most striking images of the film is the failure in Gustav’s efforts, the dripping grease from his hair and his slackened face. He ends up looking just like the queer-coded clowns he’s spent the whole film repulsed by. In the end, like most of Visconti’s characters, it is himself that he loathes the most. 8/10.

-

Braindead - dir. Peter Jackson

This shit is really tight except for the mommy issues stuff. Like I’m beyond impressed with the slapstick and gore, it’s not usually my thing but something about Braindead clicked for me.

Feels like something Edgar Wright has been failing to make his whole career. Tongue in cheek genre subversion that doesn’t feel flaccid. You can really tell Peter Jackson loves horror. 7/10.

-

The Blackcoat’s Daughter - dir. Osgood Perkins

First draft vibes. So close to liking it but if I’m being honest with myself I wouldn’t wanna rewatch this ever again. Perkins tightens up the screws on Longlegs. 4/10.

-

The Heroic Trio - dir. Johnnie To

Any “serious” review of this film would be ridiculous because to my naive understanding all that matters is that you got three bad bitches armed with guns, bombs, swords, and throwing knives fighting a evil demonic overlord who’s trying to steal babies for (NOT SURE, PROBABLY DOESNT MATTER?) reasons and he lives in the sewers and he’s using an invisible suit and psychic powers to pull it off. But I think beyond that what I loved about this film, and what I love about ALL Johnnie To’s films is the sense of camaraderie between the protagonists, it makes me feel happy inside. 7/10.

-

The Addiction - dir. Abel Ferrara

Am I defined by what I do or who I am? Is the soldier an expression of the war or is the war an expression of the soldier? Abel Ferrara asks; can the vampire be blamed or is the vampire blameless? To be a participant in the modern world requires a degree of ignorance, a willful need to abhor the violence underneath. The vampire, thus, in Ferrara’s world, is a willing sword plunging into the bowels of Hell, squelching out blood and guts as it rises out for more. Not helpless, not benevolent, just cruel and honest. 8/10.

-

Election - dir. Johnnie To

Election opens with a zoom on a holy text and a ceremonial rite, and it ends with one political candidate hitting another candidate over the head with a rock a couple dozen times, then killing his wife with a shovel, then driving his traumatized son home. All the uncle and auntie family shit doesn’t matter, all the pomp and ritual is meaningless, the world is kill or be killed. You swear on the bible so that you get carte blanche to skirt the rules, you pay lip service to tradition so you can get power. Institutional naivete will cost you, the only way to advance politically is by the adroit manipulation of the forces around you. 8/10.

-

The Kings of the World - dir. Laura Mora

Feels a bit tacky. Strong in broad strokes but the impact is reduced by the poverty porn vibe. Mora could be a great director, she just has to get out of making festival awards bait. 6/10.

-

Election 2 - dir. Johnnie To

In the first Election film, Johnnie To emphasized a binary moral order amidst the pandemonium of organized criminal ritual; there was the order, the Loks of the world, those who upheld a rational, calm, collected standard for the managerial work of the triad life. The Loks of the world sit down with their family for dinner, the Loks of the world treat their subordinates with respect and camaraderie, the Loks of the world pay their dues to the grandmasters of the organization.

By contrast, you have the Big D’s of the world, the loudmouthed gangsters who flash money to get ahead, who fly spittle at their underlings, who throw tantrums when they are arrested. At the end of the film, we see that Lok is just as violent as Big D when it gets down to it, but for most of the film we are being guided to supporting Lok over Big D because he acts more like how we expect a good “leader” to act. Only in the film’s closing moments is that narrative subverted, and Election 2 picks up thematically right where the last one ended–zero brotherhood, zero morals, zero illusions of tradition or glamor. No, in Election 2, the criminals are bought out by the police, the institution of democracy has been revealed as a sham, and the honorable Lok is just another crook trying to preserve his seat.

I don’t know Hong Kong history very well, but I sense in this film a mourning for a Hong Kong dream… the film opens with a man giving a speech about what Hong Kong means for immigrants, for dreamers, for those trying to find opportunity… it ends with the “election” being bought and sold to Jimmy, who is merely trying to go legitimate in China with his business. Basically, the dream gets bought and sold to property developers, the ritual of democracy means nothing anymore, and any romantic ideas about the triad as a brotherhood are shattered.

Johnnie To’s coldest film by far. 9/10.

-

Broadway Danny Rose - dir. Woody Allen

My favorite Woody; sad, funny, wonderful. My dad was always bugging me to watch this so I finally did and I thank him for it. Let this be a dad appreciation post. Love my father. Shoutout Jewish dads. 8/10.

-

Tokyo Gore Police - dir. Yoshihiro Nishimura

Hell is full of perverts and bug eaters, roving the subway cars groping would-be vigilantes until the vigilantes go ham and cut their wrists off at the seams, spilling their guts onto the cement. It’s so fascinating to me that Nishimura draws a direct line between trauma and law enforcement, literally getting raised by paid pigs to terrorize the public in the name of exorcising old childhood demons. Watching daddy’s head explode would fuck up any rugrat.

Nishimura paints this digital hellscape with felt-tip lens, which works to liberate the film from the shackles of good taste (nothing looks quite so skeezy as this; camcorder level footage of blood fountains and severed limbs; alligator pussy; etc) and to thrust the audience into the postmodern glare of the digital dystopia. This does not “feel” like a movie in a traditional sense, it is freed from such expectations in the same way the gamut of body mods allow for theoretical freedom. The democratization of the art from through personal cameras (which tend to be digital, not film) proliferates the medium throughout the private sector, as the police are reclaimed by the corporate world and then expanded into the military, until the money bleeds from every corner. If everybody has the tech, the one with the most money and thus access to the best tech comes on top. Techno-fascism is real, folks, it all started with Tokyo fucking Gore Police and the hits keep on coming.

Advertisements spliced between scenes add onto this postmodern glaze of media, reflecting a world which has no more delineation between flesh and metal. Solenoids indistinguishable from capillaries, bullets made of meat, every blade a toy to be sold, every gun an addendum to the face, plug and play. Even the engineers operate on flesh keys. Technology rips your face open and reprograms you, the merging happens against your will.

I find the advertisements interesting on another level because it’s almost as if we are no longer experiencing art in this film (and in the post-algorithm era, in our world) but rather being sold sensory experiences. At first pleasure is most profitable. But pleasure eventually bores the dopamine-addled mind, and so we upgrade to pain. It is no longer enough for the prostitutes to suck dick, they must now engage in sadomasochism to please their ever increasingly callous sensory economy. The salarymen no longer get off on pussy but on warped bodies and stitched titties. “You like being chewed on, right?” she says after biting a client’s penis off and turning him into a cyborg monster. Implication obvious; he does like being chewed on. He comes back with a huge engineered penis of exposed muscle tissue. Disgusting, but look at his face; he loves it. He is more than pleased with the new model.

This cybernetic hell prevents anything or anyone from truly dying, because the dead cannot be exploited, so instead the algorithm economy must revive these deceased suckers into meat puppets of death, augment their zombified souls via endoskeletal upgrades to preserve their indentured flesh for all eternity. You will work until you die, and then you will work some more. We will stretch your eyes out of your sockets to resemble those of a snail, because the fantasies only get sicker.

Nishimura dances in the ambiguity of liberation and totalitarianism just as easily as he navigates the anarchic nature of tech itself. Society may become more cruel through the proliferation of the cyborg but through technology they become more atomized from the impact of state violence, they are encouraged (through advertisements) to participate in executions via indirect remote control link. We are being brought closer to blood and yet farther at the same time. An eerie thing to think about. A cop has access to all the information, he sits in a dark empty room staring at a computer analyzing all the possible suspects; the limitless supply of data literally drives him fucking crazy. 8/10.

-

Samsara - dir. Ron Fricke

An attempt as ambitious as it is limited at chronicling in broad strokes humanity. Less about nature and more about how humans have transformed it, for better or for worse. I think I can respect the kaleidoscopic vision more if I don’t consider it to be a fully wrought out look at humanity. If this is supposed to be a cliffnotes of the human experience it may be indolent in its neutrality, I wish more strong artistic decisions were made in presenting the images. The horror speaks for itself, though, in some of them. Perhaps it is enough merely to exist as a capsule to be shown to aliens–look at who we are. 7/10.

-

Gran Torino - dir. Clint Eastwood

The old man past his prime. The preacher’s too young, the cowboys are gangsters, and everything’s stopped making sense a long time ago. America is being reborn in the hands of the refugees who’ve been defined by its history. Hmong immigrants coming into the country because of a war America fought that tore theirs apart.

At its simplest, Gran Torino is a movie about never being too old to learn, never being too old to do right by the next generation. I am a sucker for films about redemption, about looking your past in the eye and atoning for it. A gun was thrust in your hands and you were commanded onto the battlefield to die for some American ideal, and all you have to show for it is scars, gnarled skin from a lifetime of regret. 8/10.

-

The Big Lebowski - dir. Coen Brothers

Pynchonian interludes–you got the absurdity of Americana laced with weed and lovable outsiders. I rewatch this after so many years of thinking I didn’t really like it or find it funny and realize I truly was too young. I think this is a movie about Generation X, about a specific kind of failure of the American dream that manifests in Gen X. Too young for Vietnam, too old for the turn of the millennium, just old enough to bowl and settle for mediocrity.

“What the fuck does Vietnam have to do with anything?”

Walter is insane but he is sober. Vietnam is the dividing line between the America of old and the America of new–the moment in which America fully exposed itself as the aggressor, as the global police. Every war we fought before (except for the Mexican war) was easily justified and righteous, and even the Mexican war was “justified” by Manifest Destiny. Vietnam was the first time we were nakedly the bad guys.

I feel like this is the movie Paul Thomas Anderson has failed at creating his entire career. 8/10.

-

Planet Terror - dir. Robert Rodriguez

I don’t like mean-spirited pulp.

-

Gonin - dir. Takashi Ishii

Did NOT vibe with it. Ishii’s style is nails on a chalkboard to me. RAH RAH RAH. Shut the fuck up bruh.

-

Wrong - dir. Quentin Dupieux

I don’t know what cosmic coin God flipped to make me a fan of Dupieaux because in principle this is the kind of quirky random bullshit that would otherwise repulse me.

Maybe this works for me because it’s actually funny.

You’re either going to hate this or you’re gonna laugh. I’m fortunate enough to laugh. 7/10.

-

Wrong Cops - dir. Quentin Dupieux

Like Dupieux’s lesser work; funny occasionally without real direction. A quaint surreal dream sans climax. Not a fan of the one misogynoir joke. Without much else to chew on, small stuff like that sticks out. 5/10.

-

Keep an Eye Out - dir. Quentin Dupieux

Unfunny, unfortunately, in comparison to even Dupieaux’s most opaque works. The bits here just don’t land. 5/10.

-

Letters from Iwo Jima - dir. Clint Eastwood

There is a tendency among reviewers, even myself, to dismiss the war film out of hand. If it does not move us, we hand-wave it away with the oft-resorted aphorism “war is bad”, reducing the film to a mere moral–I realize this is obviously silly, but simultaneously I recognize that sometimes this is the experience of watching a war movie, the feeling that you are watching something prescriptive.

This in of itself is not a sin, a war movie can run the risk of forgoing didactics and instead playing the neutral descriptive. But I realize here, watching Iwo Jima, that my favorite kind of war film is somewhere in the middle; mythbreaking. A moral without words, a moral without actions, a moral only told through the passage of time, a story across history.

It is differentiated in a meta-analytical lens, a studio film post-9/11 that takes the side of the enemy, divorced enough from its time period to be palatable to a rah-rah jingoistic American audience. It seems almost ridiculous to imagine a patriotic American holding onto the enmity of Japan, but at the time the events of this film took place it was unthinkable to sympathize with the Japanese, let alone make a 19 million dollar studio picture taking their side. Eastwood’s point is that of a broken myth; we push young men into battle against big bad enemies, but the enemies change, the landscapes shift, the tides turn, and eventually all that is left is not the story of the warmongers but the words and sacrifices of those on the front lines.

Towards the end of the film, Saigo watches the sun set. There are two meanings I can glean from this image; Saigo on some level recognizes the end of Japanese fascism (the land of the rising sun), and the recognition of the battle’s cosmic unimportance, that the repetition of the daily cycle will cleanse the earth of its spilled blood. It is an optimistic ending, one that believes in human resilience in the face of overwhelming nationalistic mythology. Saigo, and the letters he buried, outlived his country’s fascism, and so they are the victors in the end. 8/10.

-

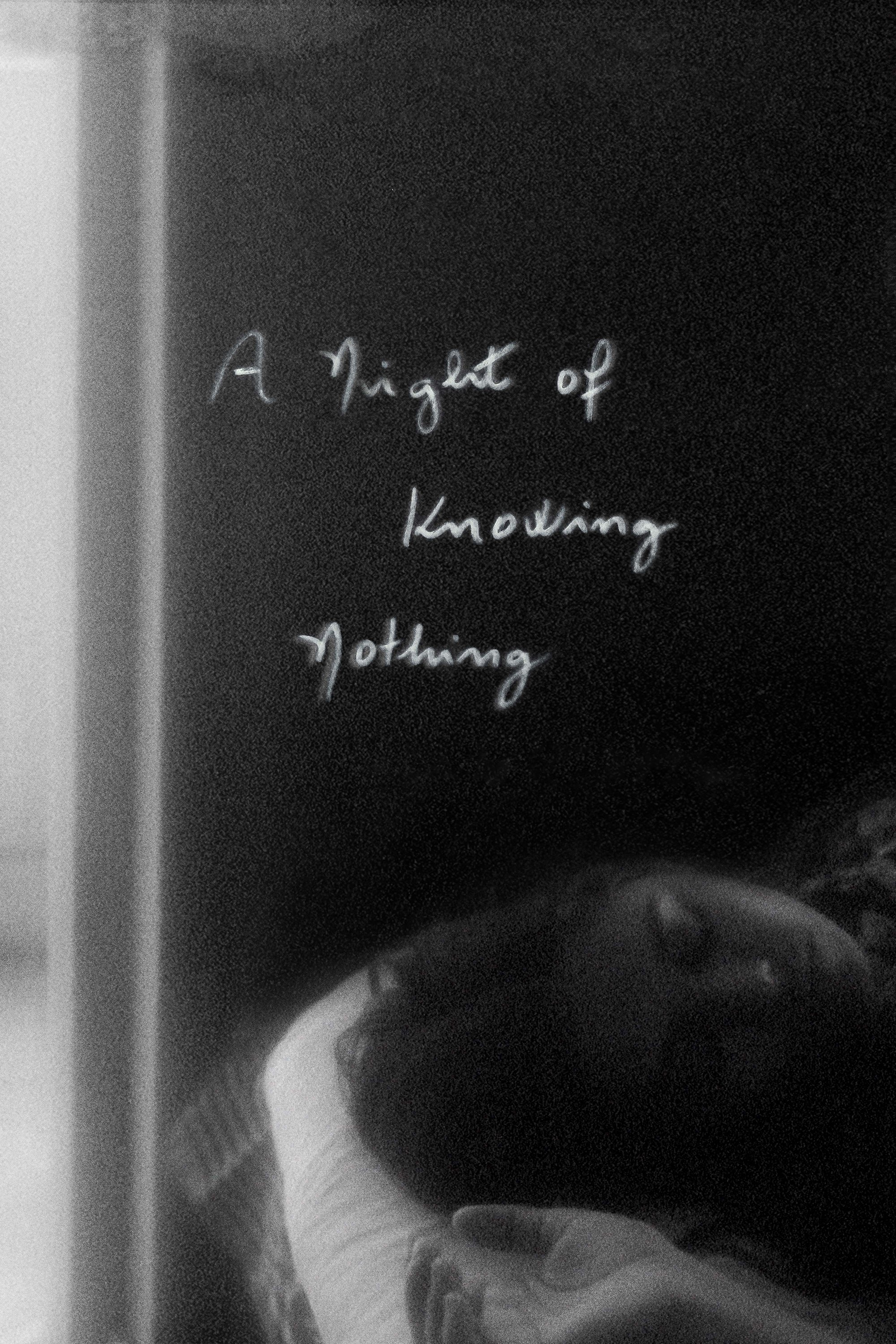

A Night of Knowing Nothing - dir. Payal Kapadia

Tonight, I write a letter that may not ever reach you. The doves that carry the words have chirped their last, the wind only sails as far as the dowry of God’s unimpeachable wallet will allow, and I write not to sing but only to talk.

Tonight, we walk under the clouded moon, a pale silhouette in smog-choked sky. You can’t see the stars, but they are there, twinkling hundreds of thousands of astronomical units away. I write to you not to reach you, because that would be impossible, but to know that in my heart I have done what I could.

Tonight, the intimacy of your dress invites me, I can picture it in my mind along with the signs you left behind on your shoulder. The imagined tattoos on the oriflamme you decked across your exposed chest. I write of your beauty not to invoke lust but to commiserate of my faded passions.

Tonight, we abrogate from the social contract, and we create a barrier through which no passenger of fate may perforate. I write of the obstacle not to inspire but to leave a mark of my participation on this Earth; proof that I contemplated the present.

Tonight, we know nothing.